|

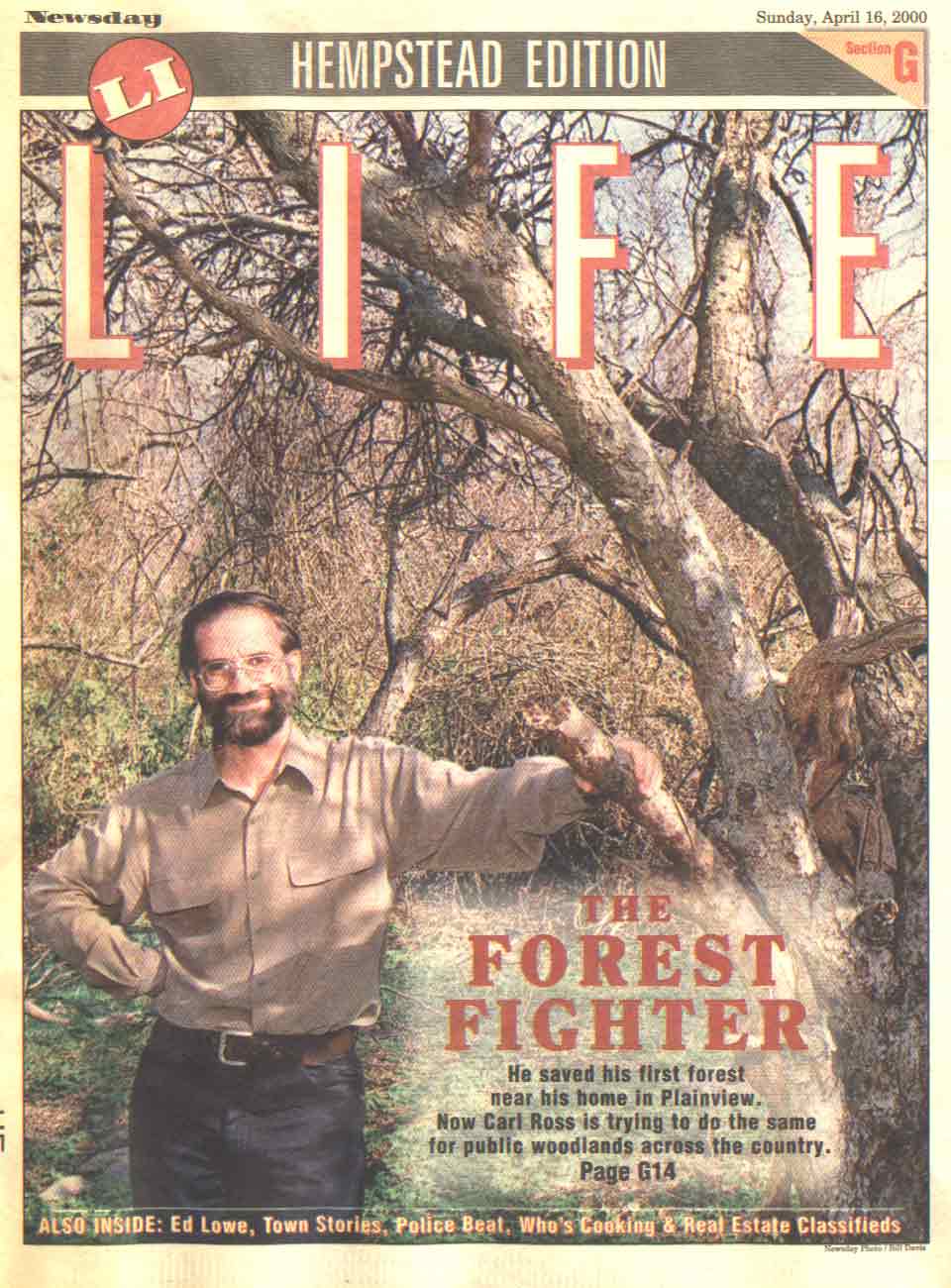

Newsday Photo/Bill Davis In a sense, Carl Ross began his career of saving America's forests right here in Manetto Hills Park, a well-treed, peaceful spot on Plainview Road, between the Long Island Expressway and the Northern State Parkway. He and high school friend Robert Adler helped save this spot from development. |

|||

|

Saving

the Forests

|

||

|

Now Ross puts in 16-hour days in a spartan office in Washington, D.C., and in the Plainview home he inherited from his parents, toiling thousands of miles away from the great ancient forests he has never seen but fights passionately to protect. And he operates at an even greater distance, philosophically, from the cozy world of the large and long-established environmental groups who regard him as a loose cannon and an uncompromising zealot. Yet Save America's Forests, the group Ross started 11 years ago in his Long Island living room, has become a leader in one of the highest-profile environmental issues of the year: the campaign to drastically reduce logging in the federal government's 155 national forests, which collectively cover an area nearly twice the size of California. Ross is the driving force behind an anti-logging bill that has more support in Congress than any other version, including one backed by the much larger Sierra Club. He hobnobs with celebrity supporters such as scientists Jane Goodall and E.O. Wilson and actor Ed Begley Jr., and his heretical attacks on the environmental movement's usual allies in the Clinton administration, including Vice President Al Gore, have gotten him front-page attention.

Not bad for a skinny, intellectual kid who was too restless to finish college and didn't figure out what he wanted to do with his life until he was 36. "I did it my own way. I'm not the Western guy; you know, the big hiker or camper. I didn't finish at Columbia. I didn't go to law school. I didn't do those things," he said. "I just looked at life in a different way." Picking over his toast and orange juice at the Plainview Diner on a damp spring morning, Ross ruminated on his winding path to an unlikely career as a fighter for wild open spaces who lives in a place where there's no true wilderness left. "There are some nice parks on Long Island, some nice places to go hiking. But basically, I realized I had grown up in an area that has been ecologically impoverished for centuries," he said as traffic crawled by outside on Old Country Road. "That's why I'm trying to preserve these last ancient forests and restore these other wilderness areas, because I've seen what happened here on Long Island." Like many other communities near the Nassau-Suffolk line, Plainview was a work in progress in 1957 when Abraham and Jeanette Ross arrived from Brooklyn via New Jersey. The potato and vegetable farms were disappearing fast, but the rural crazy-quilt landscape of field and forest had not yet given way entirely to the fastidious needlepoint of the postwar suburb. Young Carl watched the bulldozers dig out the footprint of his family's home, and played with his toy trucks in the front yard as a cement mixer poured the foundation. When the house was ready and the family moved in, he spent much of his time outside. If he wasn't watching the construction teams putting up identical split-level houses elsewhere in the neighborhood, he was exploring the woods at the community's edges.

|

|

||

Newsday Photo/Bill Davis The Capitol Hill office of Save America's Forests puts Ross right within lobbying reach of lawmakers.

|

"To

grow up on Long Island at that time was wonderful, because you still had

this great, vast outdoors. There was so much countryside all around. All

of it was exciting. And all the development was a thrill, too, because when

you're a kid it's exciting to see all the machines, and the roads and the

houses going up," he said. "You don't know yet about the downside of what

all that development brings."

It would be a stretch to call them tree-huggers, but the Rosses were appreciators of nature. Abraham, a graphic artist, painted outdoor scenes for recreation, and Jeanette, a second-grade teacher, was an amateur photographer whose work was displayed in the family's living room. When Carl was a baby, she took him for strolls every day in Prospect Park or the Brooklyn Botanical Garden, and introduced him to Smokey Bear on a summer trip to the National Zoo in Washington. Jeanette also made sure the front and back yards were full of trees, planting hemlocks, two sycamores and a blue spruce. (Carl, ever the advocate for wild things, likes to point out that many of the ornamental trees his mother planted are dying from disease or pests, while a maple and pine tree that began as weeds are thriving on the home's front lawn.) Since the family didn't go camping or take trips to Yosemite, Carl got most of his early ideas about nature and the West from the popular culture of the day. Lincoln Logs, Dr. Doolittle, episodes of "Wild Kingdom" -- he counts them all as early influences. "I grew up thinking that the cabin in the wilderness is the American ideal," he said.

|

||

|

|||

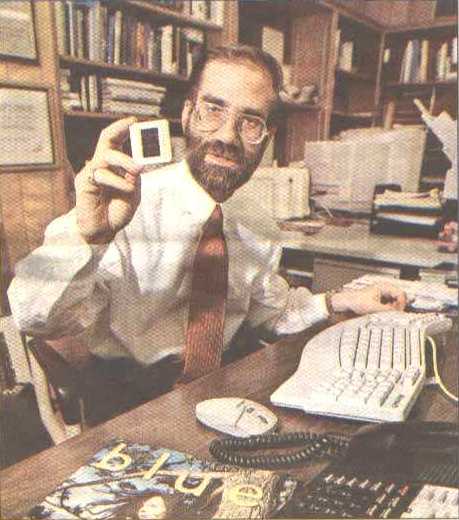

Newsday Photo/Bill Davis Ross, a proponent of legislation reducing the cutting of trees in national forests, does his homework at his desk in his Washington, D.C., office. |

Feeling

restless, Ross left Columbia after a semester and bounced around the Northeast,

periodically returning home to Long Island. Wearing his longish hair in

a ponytail, he worked for a while at an organic blueberry farm on Cape Cod,

and volunteered at the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation upstate, helping to

rebuild a barn. He agonized over the draft, but decided to register and

was not called. And back home in Plainview in 1972, he found a cause in

the fight to preserve one of the last large open spaces in the community,

the Shattuck Estate. Nassau County had bought the 138-acre parcel just north

of the Long Island Expressway, and there was talk about turning it into

a golf course, or possibly selling it for a housing development. Ross and

some of friends had a different idea: They thought it should be a nature

preserve.

"All our parents thought we were just nuts. They thought it was a noble cause, and a bit cute, but that it would never happen," recalled Robert Adler, now a professor of environmental law at the University of Utah. The students circulated petitions and put out a newspaper called The Hard Times featuring an article by "Chuck" Ross that was equal parts Abbie Hoffman and Johnny Appleseed. "We continue to slaughter, to clear-cut, to poison, to pillage," he wrote. "We must deflate our ego-centric view of ourselves vis-a-vis the universe. Enrich the soil, plant a garden and fight." The ruckus they stirred up convinced the county to shelve its plans to develop the property, and even though other building proposals have surfaced over the years, today the estate, known as Manetto Hills Park, is the nature preserve Ross had envisioned. "It's very satisfying to know we accomplished something," he said. |

||

|

|||